Trauma, Memory, Resistance: Healing in a Wounded Nation

You cannot heal a wound you refuse to name.

Cocktails Archibald Motley, 1926, via Art History Project

The Wound Beneath the Skin

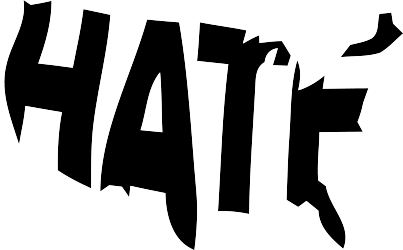

America is a nation in denial about its wounds. The traumas that shaped this country—slavery, genocide, segregation, displacement, mass incarceration—have never healed because they have never been acknowledged. Instead, we are told to “move on,” to “look forward,” to “let it go.” But you cannot heal a wound you refuse to name. And the longer it festers beneath the surface, the more it poisons everything it touches.

Trauma in America is not just psychological; it is structural. It lives in segregated neighborhoods, polluted water systems, overcrowded prisons, and underfunded schools. It lives in racialized patterns of illness and premature death, in homelessness born of economic violence, in the unequal grief that determines whose suffering makes the news and whose doesn’t. These are not coincidences—they are symptoms of a body politic that has never tended to its injuries.

Collective Trauma and the Politics of Denial

In public health, trauma is often described as an exposure to a threat that overwhelms the body’s capacity to cope. Collective trauma works the same way—it overwhelms the capacity of a people to feel safe or whole. The United States has experienced centuries of such trauma, yet its systems are built on repression, not repair.

Every time the nation averts its eyes from police violence, refugee detention, or the ongoing dispossession of Native lands, it reenacts its founding trauma. Denial becomes policy. The “bootstraps” myth becomes anesthesia—a convenient sedative that dulls public empathy by reframing systemic violence as poor personal choices. It allows lawmakers to defund schools, poison water, close hospitals, and militarize police while insisting the harmed simply “try harder.” And so the nation drifts further from itself, mistaking cruelty for discipline and inequality for natural order.

That’s how systemic inequities are maintained—not only through overt harm, but through the refusal to witness harm. Environmental racism ensures Black and Indigenous communities breathe toxic air and drink contaminated water, while politicians call it a “zoning issue.” Maternal mortality rates for Black women remain three to four times higher than for white women, yet we call it a “disparity” instead of what it is: a consequence of structural neglect. The trauma is continuous, not historical.

The Memory of Harm

Memory is the bridge between trauma and healing—but it is also contested terrain. America’s memory is curated for comfort. Textbooks soften the language of slavery, museums tell half-truths, and whole chapters of Indigenous and immigrant histories are omitted entirely. The result is not just ignorance—it’s cultural amnesia that protects power.

The fight over memory is a fight over whose pain counts. When communities demand truth-telling—about lynching, about medical experimentation, about the theft of land and labor—they are not being divisive; they are demanding the right to heal. Because without collective memory, there can be no collective recovery. Memory lives in the body; collective memory lives in the world.

Individual memory is the quiet archive we carry inside us—the sensations, stories, and scars that shape who we are. But collective memory is different. It’s the story a society tells about itself: what it commemorates, what it buries, what it sanitizes, what it refuses to speak aloud. When personal truth meets public acknowledgement, healing becomes possible. When the gap between the two widens—when survivors remember what the nation prefers to forget—trauma festers. The work of justice is the work of closing that gap.

…