The Robbery at the Louvre is a Lesson on Hubris

“A woman caresses the ‘Sleeping Hermaphroditus’ sculpture, 1980” via L’Officiel

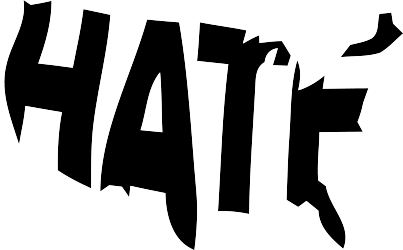

The Louvre was robbed. It took less than eight minutes to remove what France held in infamy for centuries. The country has a history of stealing, and the theft left the country a bit scandalized. Some historians were heartbroken, but many casual observers thought the museum and the country got what they deserved.

In the days that followed, it was clear that the Louvre had already been aware of its poor security. The jewels, being invaluable, were not insured. Security in museums maintains the integrity of the visuals. They ensure that the oils from our hands aren’t aging the paintings, that the flash from our cameras doesn’t cause pigments to fade, and that jewel thieves don’t get away with royal crowns.

Nevertheless, France was embarrassed as the world looked on.

The obvious irony is that the French took ownership of many of their art pieces because they simply wanted to. The art’s creativity was its attraction, and its belonging to someone else was the allure. It was a symbol of dominance and of strength. It reminded the world that France was the winner. Napoleon Bonaparte wanted the Louvre to be a center of genius, and it was his goal to put on display “the greatest masterpieces of art.” He employed violence to take what he wanted in order to do so, and in so doing, he acknowledged the beauty and mastery of the conquered and implied that part of France’s greatness lay in its ability to possess the creations of others.

Now, when jewels have been stolen and they have yet to be retrieved, France’s past and the story of the creation of the Louvre continue to work against their claims for sympathy. The robbery at the Louvre reminds us that the person who has the power is the person who chooses to take it. The concept isn’t inconsequential, but it is curious to see how institutions respond to the same act that made them famous in the first place.

…