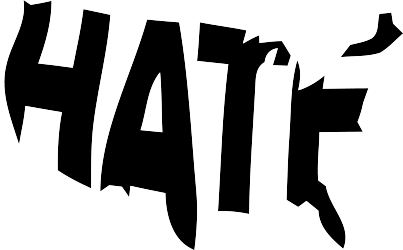

The Unseen War in Chocó and Its Denied Racism

(A tweet from @LUISEROLAVE that states "Quibdó is bleeding and our mothers are weeping!" accompanied by an image of demonstrators in a protest denouncing the unlawful killings of social leaders in Quibdó.)

By Carolina Rodriguez Mayo

Since 2021, Colombia has faced an acute social crisis. Several unjust situations, including the pandemic, and poor management from current President Ivan Duque have resulted in the longest general strike the country has seen. From hospitals to streets, from roads to social media, people from Colombia were making their voices heard. One of the hardest moments in this social upheaval involved Afro-Colombian regions where it became clear that structural racism and government negligence would result in the death of many. The crisis during the pandemic mirrors the crisis we see today: Afro-Colombians encounter significant violence on a daily basis.

Chocó is a region in Colombia located in the Pacific. It has been a point of interest for colonizers, government leaders, guerrillas and criminals of all kinds because of its rich soil, highly advantageous location and ports. However, Chocó has been overlooked for years. Its land has been mostly exploited because the majority of its population is made up of Black/Afro-Colombians. Consequently, it also faces injustices rooted in racism, such as the conflict that is being ignored right now by the Colombian state, which facilitates the death of many innocent Afro-Colombians.

The strike of 2021 exposed how the country has been turning a blind eye to its most vulnerable people. Places like Valle del Cauca, Cauca and Chocó showed the world how the lack of follow-through with the peace process had resulted in the emergence of drug trafficking criminal groups which exploit people and the territory. According to a 2021 report published by ACAPS, 43% of the territory in Chocó is used for illegal gold mining. This practice is the main source of financing for both armed insurgent militias —such as ELN (National Liberation Army) and FARC-EP (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia-People's Army)— and drug cartels that operate in the region. Both the militias and the cartels have waged wars to try and seize full control of mining operations in Chocó.

Last January, leaders of the Catholic church, in association with social leaders of the community of Chocó, reported how unbearable the violence was. In response, the government dismissed the reports, claiming that the violence seen in Chocó was merely limited to isolated cases. The reality lies far beyond that claim. The population, social leaders and the church communicated that what was happening in Chocó was a systematic and chronic problem, not an exceptional incident, especially when considering that violent groups like ELN are using this region to further advance their drug trafficking business.

While there is no lack of law enforcement presence (with approximately 5,000 soldiers and police officers in the area), citizens were not guaranteed protection. Quite the opposite, many soldiers and police officers worked in tandem with the paramilitary; the same paramilitary that has been thriving in Chocó thanks to the support given by these law enforcement bodies.

On top of that, the capital of Chocó, Quibdó, has been deprived of its main hospital, San Francisco de Asis, since March 7, 2022. Its employees are currently on strike because…

Carolina Rodríguez MAYO was born in Bogotá, 1991. Traveler, educator and writer. She has experience as a teacher, translator, editor and writer. She lived in Brazil, Mexico and Turkey. She has published her work in Colombian magazines such as Literaridad, Sombralarga and Sinestesia. She was chosen as part of an anthology of young poets, Outcrops, the bridges back to the past are broken published by Failed Editors. Her poetry has been in places like Brown University and on the People who read stories podcast.