Juneteenth and the Radical Abolitionist Harriet Tubman

Portrait of Harriet Tubman taken by Harvey Lindsley in Auburn, N.Y. between 1871 and 1876?, printed between 1895 and 1910.

On April 27, 1860, Harriet Tubman, with a group of activist abolitionists, coordinated the rescue of Charles Nalle. A fugitive of slavery, Nalle made way from Virginia to Troy, New York, where federal marshals and police captured him. Tubman disguised herself as an elderly woman, and the back and forth between slave catchers and the Troy community included a gun battle and an escape by riverway. At the end of the events, Tubman and the community helped raise the funds to purchase and ensure Nalle’s freedom.

So, in the midst of the historic everyday heroism of an extraordinary woman, who would have thought that so close to Juneteenth—a holiday celebrating the formal abolition of slavery and commemorating the liberation of enslaved people in Galveston, Texas on June 19, 1865, three months after in the end of the US Civil War—that I would be writing to prove Harriet Tubman’s existence.

Juneteenth and abolition celebrations are the core of the history, triumph, and resilience of Harriet Tubman and Black ancestors in the United States and the Western Hemisphere who survived and fought to end formal chattel slavery.

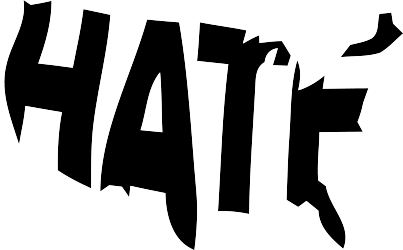

Tubman has been the target of such unnecessary animosity and hate for dreaming of a world that still does not truly exist, but that many activists who have taken on her vision are still fighting for. She was a radical abolitionist who fought for her liberation, the liberation of her community, and all Black people in her midst. The problem too many people have with Tubman is her legacy.

Just like the hundreds of Underground Railroad “conductors” she trained at the height of the abolitionist movement, presently, there are millions of modern-day abolitionists and activists just like her throughout the world who work every day for sustainability, community, and question and fight against systems of supremacy and tyranny. She refused to meet with Abraham Lincoln during the US Civil War when he and others introduced a scheme for the mass deportation of formerly enslaved and free Black communities. She stood on business and did not deviate from the full freedom and liberation of her people.

This piece is a response to the “haters.” Kanye West (of course); the white woman who is suing a public library for not allowing her one-woman-show of Tubman’s and other notable Black women's lives (wtf); the US government for taking down information about Tubman from the official National Park Services website; the random people on Harriet Tubman’s internet saying she is as real as the Easter Bunny (what the helly…); even the writers of the 2019 Harriet film that misrepresented Harriet Tubman’s story (60% fiction); people advocating to place her image on the 20 dollar bill (she wanted REPARATIONS not representation…); the political wannabes that use her sacred name in vain; and the countless history textbooks that limited her story to a simple byline, “Harriet Tubman freed slaves.”

Harriet Tubman stood about five feet tall. She was a disabled, formerly enslaved Black woman without the ability to read and write. There is no mystery to Tubman’s story; however, the power of her liberatory narrative is continuously silenced and repressed…