What Now? The U.S. to Deport 521K Haitians

François-Dominique, Toussaint Louverture, Via Europeana.eu

On February 20, President Donald Trump’s administration revoked the extension of Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for Haitians, just weeks after revoking TPS for Venezuelans. Haitian nationals who have used this opportunity to leverage what the United States offers are now left to decide, with no real direction, what happens next.

The partial vacation of the notice that extended and redesignated Haiti for TPS shortens the protection by six months. The easy-to-read version: Haitians with TPS will no longer be protected against deportation after August 3, 2025. Originally, their status would have expired in February of 2026, with the possibility to renew.

Kristi Noem, Secretary of Homeland Security, emphasizes the “temporary” status of TPS in her decision. "President Trump and I are returning TPS to its original status: temporary."

A Department of Homeland Security representative mirrored the position, “Biden and Mayorkas attempted to tie the hands of the Trump administration by extending Haiti's Temporary Protected Status by 18 months—far longer than justified or necessary.”

In the case of Haiti, UNICEF has reported a 1000% increase in sexual violence against children. Gangs overrun 85% of the nation’s capital, and fair, democratic elections have yet to occur since the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse in 2021. Many would argue that it’s been longer. Children are being recruited into gangs. And, a Kenyan UN Peacekeeper was recently killed.

TPS is still necessary.

The representative went on to say, “We are returning integrity to the TPS system, which has been abused and exploited by illegal aliens for decades.” People in the U.S. on TPS are here legally, and using the system for support is not exploitation—it’s the very reason it exists. Needless to say, the use of the word “alien” to reference foreign-born people has issues of morality in and of itself.

TPS has been around since 1990. It was created in response to political turmoil in El Salvador and protects nationals from designated countries from similar turmoil or environmental disasters. Haiti was first designated as a recipient country in 2010.

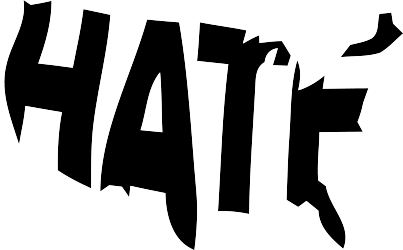

The emphasis on the word “temporary” now serves as more of a misnomer than an accurate portrayal of the designation. In the Trump administration’s pointed target against foreign-born persons, Haiti seems to exist in the crosshairs of Trump’s need to both whiten the country and undermine Biden’s legacy.

What does Deporting 521,000 Haitian Immigrants Look Like

I spoke with immigration attorney Yasmin Blackburn, and she says she has seen a dramatic uptick in consultations. “My Venezuelan and Haitian clients are scared. There is a plethora of misinformation and often they don’t know where to look.” Blackburn went on to say, “Recipients of TPS are immediately vulnerable to deportation and exclusion from the United States despite their significant contributions to the U.S. and its economy. Depending on how the person entered the U.S., their temporary legal status is at risk without any path forward to legal status.”

The original extension and redesignation of Haitian nationals and those who “last habitually resided in Haiti” gave folks an opportunity to apply or re-register for TPS. Now, the options are unclear.

Haitians have contributed to the United States' landscape for centuries, from supporting the Revolutionary War to founding Chicago. However, the geopolitical relationship has always been one-sided. It's important to understand the nuance of poverty and why there's a vested interest in Haiti being underdeveloped to the benefit of the US. Its proximity allows for U.S. business owners to flourish (see: Citibank; see: post-earthquake relief; see: agricultural reform; see: forced eradication of Creole pigs), while citizens experience the opposite.

Returning recipients of TPS to Haiti right now could look a number of ways.

The current administration has admitted to deporting Venezuelans without due process and without substantive evidence. Most recently, a tattoo was used as a means to deport a Venezuelan man to El Salvador. I wonder if the same will be done to Haitians under the opaque veil of safety. However, Venezuela does not accept deportees, and Haiti does. Currently, the U.S. is paying El Salvador $6 million to house 300 Venezuelan deportees for a year. The payment for the movement of bodies increases the likelihood of guilty verdicts and provides an incentive to continue skirting the law.

What Returning to Haiti Could Mean

Since January 2025, the Trump administration has dismantled the US Agency for International Development (USAID). Haiti is one of their largest recipients, receiving over $300 million in aid.

So, having undermined the rule of law in Haiti to create a pathway to some level of reprieve, only to then return people to a country that is still in the process of development, is a cyclical act. It is a strategic one. And it is an inhumane one…