Collective Amnesia: The Weaponization of Forgetting

Forgetting isn’t harmless—it’s the oldest American weapon.

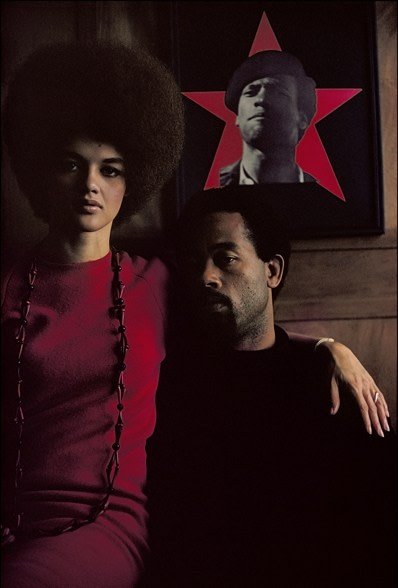

Gordon Parks, Eldridge Cleaver and His Wife, Kathleen, Algiers, Algeria, 1970 via Gordon Parks Foundation

Forgetting as Strategy

America has never been forgetful by accident. Forgetting is one of its oldest strategies of survival—for the powerful, not the people. This country doesn’t suffer from memory loss; it suffers from selective recall. It remembers who built the skyscrapers, not who built the railroads. It remembers who signed the Declaration, not who was enslaved when it was written. Forgetting here is not a lapse—it’s law.

From sanitized textbooks that call slavery “involuntary relocation” to monuments that glorify traitors as heroes, America has weaponized amnesia. Forgetting maintains the illusion of innocence. It’s how a nation can praise freedom while building its wealth on unfree labor. It’s how people can inherit privilege without guilt and oppression without accountability. Forgetting is the anesthetic that dulls the collective conscience, keeping us numb enough to repeat history under a new name.

Erasure as Violence

To forget is not passive. It is violent.

Erasure is not the absence of memory—it is the deliberate destruction of it. It is a form of narrative warfare, waged not with guns, but with omissions. It kills slowly, through textbooks, headlines, and silence.

When the Tulsa Race Massacre was burned out of history books, that wasn’t an oversight; it was an act of protection—not for the victims, but for the perpetrators. To erase is to conceal guilt, to protect comfort, to rewrite the crime scene and let the same structures stand. When the bones of enslaved people were unearthed beneath American universities, the question wasn’t how they got there—it was why no one ever asked who they were.

The violence of erasure is also generational. It fractures belonging. It severs identity from history, leaving descendants with the ache of something missing they can’t quite name. Children grow up believing they come from nowhere because the system insists their ancestors never existed. It’s a public health crisis masquerading as pedagogy—because what does it do to a body, a community, to live perpetually unacknowledged? Trauma without witness calcifies; grief without language becomes illness.

And so erasure is both historical and ongoing. It lives in the unmarked graves of Indigenous children, in the missing data from Black maternal mortality studies, in the disappearance of queer and trans lives from public health surveillance systems. Each omission is an administrative act of violence—a quiet decree that says: you do not matter enough to be counted.

The state erases in order to keep order, which often aligns with white supremacy. Media erases to maintain marketability. Education erases to preserve the myth of moral progress. Together, they ensure the violence never looks like violence—it looks like forgetfulness. It looks like peace. But peace built on silence is rot disguised as stability.

Erasure kills twice: once in the body, and again in the story. First through the original act of harm, and then through the ongoing refusal to name it. Healing begins only when someone dares to remember out loud.

Tulsa Massacre: “Sifting through the ruins of Greenwood’s Gurley Hotel, a photograph by Reverend Jacob H. Hooker, a survivor of the massacre, whose photography studio was burned down and never rebuilt” via Public Domain Review

Monuments, Memory, and the Manufacture of Myth

Walk through almost any Southern town and you’ll find stone men on horses guarding courthouses, towering over the descendants of those they enslaved. These monuments aren’t neutral—they are propaganda carved in granite. They were erected not in the wake of war, but during Reconstruction and Jim Crow, as reminders of who still ruled the soil.

America builds monuments to power, not to truth. It immortalizes the aggressor and silences the survivor. But in Montgomery, Alabama, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice—dedicated to victims of lynching—stands as an antidote. It doesn’t invite nostalgia; it demands reckoning. Each suspended steel column carries a county name, a number, a memory. It reminds us that the soil itself remembers, even when the nation refuses to.

“More than 4,400 Black people killed in racial terror lynchings between 1877 and 1950 are remembered here. Their names are engraved on more than 800 corten steel monuments” via The Legacy Sites.

Also, Why Build a Lynching Memorial?

The Machinery of Forgetting

Forgetting requires maintenance. It is engineered through curriculum boards, sanitized films, and political bans on “divisive concepts.” When politicians claim that teaching truth will make children uncomfortable, what they mean is: the truth will disrupt the comfort of the powerful.

The machinery of forgetting is efficient. It runs through algorithms that flatten protests into hashtags and through headlines that turn massacres into “incidents.” It hides the throughline between slavery and incarceration, between redlining and homelessness, between genocide and gentrification. The cycle continues because forgetting is convenient—it absolves, it anesthetizes, it keeps power intact.

But what happens to the body politic when the lies become too heavy to hold? What happens when the silenced start to speak again?

Residents and protesters clash with federal agents in Chicago’s East Side neighborhood on October 14, 2025. Via CNN Joshua Lott/The Washington Post/Getty Images

Resistance as Healing

We often imagine resistance as protest in the streets: raised fists, chants, and confrontation. But resistance is also quiet. It lives in memory. It hums in the rituals of the living who refuse to let the dead disappear.

Resistance is a grandmother telling her grandchildren the stories that the state erased. It’s a community preserving a language banned by law. It’s a mural painted on the side of a building where a person was killed. It’s a song sung at a funeral when there is nothing left to say.

These are acts of resistance—but also of healing. They stitch back what erasure tried to tear apart. They rehumanize what history dehumanized. In public health, we speak of trauma as generational. So too is healing. Every act of remembrance interrupts the transmission of pain and rewrites the inheritance.

Healing, then, is not a retreat from struggle—it is the continuation of it by other means. It is love as defiance. It is memory as medicine.

…