Activism III: Activism Is Not Monolithic

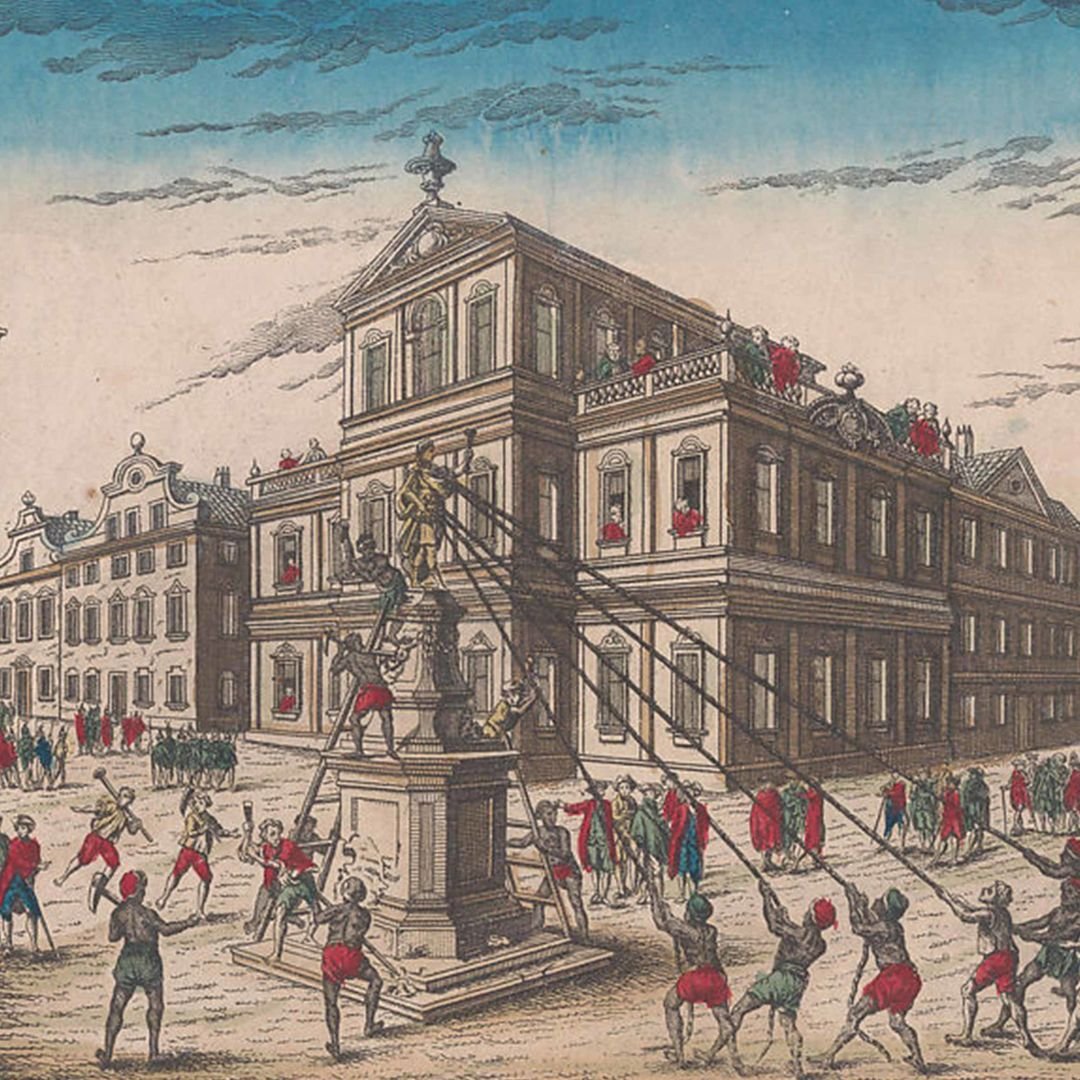

Franz Xavier Habermann (German, 1721–1796). Destruction of the Royal Statue at New York, July 9, 1776, after July 1776. Via: The Met

I’ve been an activist for as long as I can remember—though I didn’t always understand that. Activism can be defined as “a doctrine or practice that emphasizes direct vigorous action especially in support of or opposition to one side of a controversial issue.” My journey into activism was not defined by any grand campaign but rather by the quiet moments that shaped my understanding of navigating the world in community, for community, by community.

I am a biracial Black woman. My rich and diverse heritage stems from my father's roots in Texas via Northern Africa and my mother's lineage from Guam; she is of Dutch, Italian, and Chamoru ancestry. I was born in San Diego, CA, but my family moved to Guam when I started kindergarten. Guam is a place that survived 300 years of colonization, only to be colonized once more by the US under the guise of military liberation. The US occupation of Guam meant trauma wrought on its people —the accumulation of native Chamoru people’s lands, the rape and impregnation of native women, the erasure of the native tongue, and the forced assimilation to Westernized religion.

Growing up on the small island of Guam, I was immersed in a culture that valued community and mutual support. Two key concepts, chenchule’ and inafa’maolek, deeply influenced my perspective. Chenchule is a traditional Chamoru system of social reciprocity that emphasizes support and care for one another within the community. It's about families coming together to meet each other's needs, fostering a sense of deep devotion and mutual assistance. Inafa’maolek underscores the importance of interdependence, highlighting the community's collective well-being over individual interests. These principles teach us that by leveraging our collective power, we can work toward justice and overcome the inequities that affect us all. Further, this taught me that activism is not merely a set of actions; activism is life itself.

Examples of subjugation, inequity, and revolution have marked history for a millennium. If our ancestors endured colonization and the transatlantic slave trade, we can surely summon the courage to resist in our own ways. Resistance takes many forms, from protests and advocacy to organizing and direct action. It challenges oppressive systems and promotes equality, justice, and positive change. Activists mobilize people, raise awareness, and work towards specific goals that align with their values and beliefs.

I have found that my identity and upbringing are deeply intertwined with my activism. It is not always characterized by grand displays of defiance. Instead, activism manifests as a fervent commitment to nurturing and safeguarding the community's well-being. Within this framework, community is not merely a geographical or social construct but a profound sense of interconnectedness.

In the US, our present struggles are a continuum of resistance against injustice—from slavery to Jim Crow to George Floyd— it’s a way of life ingrained in the fabric of our existence. In embracing community care as activism, I find solace in the knowledge that every act of compassion, every gesture of support, is a step towards a more just and equitable world. It's about leveraging our collective power to dismantle oppressive systems and strive for justice, drawing strength from our shared histories of resilience.

That being said, activism takes on myriad forms. Martin espoused direct action through peaceful means, Malcolm less so. The Panthers were both militaristic and community-focused. Whatever resistance looks like for you, the most important thing to remember is that the consequences of apathy in the face of oppression allow the status quo to march on. We owe more to the strength of our ancestors than that.