With Great Privilege Comes Great Responsibility

With Great Privilege Comes Great

Responsibility

AHUS X Ravneet Vohra

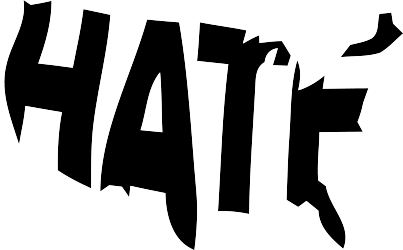

AHUS spoke with Ravneet Vohra, founder and CEO of Wear Your Voice (WYV), the intersectional feminist publication. We chopped it up about why she launched WYV, how she’s been able to obtain incredible writers on her roster, where she sees the publication in the future and why she corrects white people on how to pronounce her name.

Ravneet started WYV out of Oakland in 2014. She studied at De Montfort University Leicester, UK, obtaining her Bsc Hon in management science in 1997. The CEO’s background is anything but traditional. She’s worked as a merchandiser for a mainstream retail company, and went on to work for a high-end fashion house, Belinda Robertson, as in house sales, marketing & PR, she’s also a nutritionist and a personal stylist. Despite quickly advancing in the fashion industry, something didn’t sit right with Ravneet. “It was as if things came full circle from when I was a girl, looking at magazines and not seeing anyone that looked like me.”

Value Given, Not Earned

Ravneet lived in Kingston Upon Thames, UK. Her family is Sikh (pronounced “sick”) and lived in a predominantly white neighborhood, where the school she attended mirrored such.

“From day one, I recall always being an object of interest growing up,” she told us. Ravneet was an anomaly for both her classmates and her family. “Because I was one of few Desi girls, in a school filled with mostly white faces, the other students bombarded me with questions: why is your hair so long, why is your skin so dark, why do you smell like curry?” She laughed to herself. Prodding, which made her feel like she was strange or some type of creature. “But when I’d return home, it was the opposite,” she continued, “I was praised for my looks. Then, I had long golden brown hair and light skin, granting me white passing privilege.”

Ravneet confides that her earliest viewpoints on beauty came from her own community. “The real problem started from within our own culture. The Sikh community aspires for Eurocentric beauty standards,” she sighed. “The fact is, our skin and hair are generally varying in shades of color, from dark brown to light brown. Nonetheless, because of my lighter skin, I was given value.”

At family events, she was praised for her complexion and family echoed how beautiful she was. Any value that was given however, stopped at her appearance.

“Being a girl, I didn’t seem to have any value when I opened my mouth. Traditionally, Desi girls don’t have a voice in their family and are raised to be submissive. Moreover, we’re somewhat bred, to be married off to the highest bidder.”

Hence, Ravneet faced two different worlds each time she stepped out her door in the morning and returned back in the afternoon. The former, where she was made to feel less than by her white counterparts and the latter, where she was measured solely by her looks.

Losing Her Voice

In Ravneet’s South Asian community, boys were regarded higher than girls. Conversations seldom centered around girls, which probably served as a hindrance for four-year Ravneet to speak her truth.

The sexual abuse of Ravneet started at that very age (and continued for years after).

“Honestly, I was intrigued by it (the abuse) like a lot of abuse victims are,” she explained. Her abuser was a married man and the abuse happened in his home. “My abuser, to lure me in, asked if I wanted to see magic. And, c’mon, what child doesn’t want to see magic?”

Those that assumed the duty to protect her failed. It is common for children, let alone most adults, to shoulder blame of the abuse done to them. “For a long time, I thought I called it on myself,” she explained. “I thought perhaps maybe it was because of the way I looked or behaved, that I somehow encouraged it.” That notion likely was reinforced after the wife of her abuser walked in on the assault and blamed, Ravneet, but not her husband.

“I didn’t have the words or the courage to push the adults around me to understand that what was happening to me was in fact wrong.”

“I lost myself. I lost everything I was before then. I lost my voice.”

Ravneet Vohra

Finding Her Voice

It would take Ravneet some time to find herself again after the abuse.

She would go on to university but had difficulty adjusting among her peers. On top of the normal problems most young adults face (acne, adulting, etc.), Ravneet continued to battle with the silence that went unaddressed.

“It was important for me to express what I needed, what I wanted and how I felt. But I’d trace back to my four-year old self, remembering that I had not been taken seriously then.”

Although academia offered her more diversity than she had been used to, with Black and Brown faces sharing the same space, she had yet another hurdle.

“I had difficulty socializing with men. I felt I was only good for one thing!” Ravneet avoided eye contact with men whenever possible. “I felt my only value to them was sexual. And not as a humxn, who has a voice [but as a thing].”

This would lead to her not respecting her own body. Things unfortunately got worse before they got better.

“As my body grew and I expanded as a womxn, I began to feel not as attractive as my white counterparts.” The source for those insecurities primarily came from fashion magazines. Ravneet continued, “the magazines served no source of inspiration as all I saw were white bodies. And the subjects boxed us in as just sexual objects, sexuality is fine, but 5 Ways To Give The Best Blowjobs spoke to some people but it didn’t always speak to me. I wanted more, I needed more, and I decided that I could give this industry something it didn’t always see, hear or read.”

Approximately 20 years later, beauty (and the standards of it) had not changed since she was a child. White bodies. Tall, skinny, white bodies defined what beauty was. It dawned upon Ravneet, “if I wasn’t represented, then there were a whole bunch of other people who looked nothing like me that also went unrepresented.”

Next came a challenge that no one tasked her with but instead Ravneet posed to herself, “What am I gonna do about it?”

I Put My Privilege Where My Mouth Is

Ravneet may have lost herself at the age of four but she never abandoned that four-year-old. She always knew that she would one day re-emerge and be free of fear. Her return came in the form of broken silence and the publication to be called: Wear Your Voice.

When posed with the question (that she asked herself): “what am I gonna do about an industry that ignores and erases marginalized people?” The answer was clear, she would be the one to disrupt things herself.

“WYV was born through my own silence, and was made in my daughter, Ambika’s name. Moreover, it was made for our children so that they could have a safe space. They should have a safe space where they can get sound content and advice. They should have a safe space without the threat of constant pressures of being pretty or skinny or white or tan being shoved down their throats.”

This endeavor, niche as it was, launching an intersectional feminist publication, was not easy.

“I bootstrapped WYV for the first five years and nearly lost my home in the process,” she expressed with a humbleness in her voice. Her objective, initially, was to build an authentic brand, built on integrity so that they could develop a solid foundation and if investors were ever to invest, they would have no input on what was published.

Ravneet expressed that WYV could only operate under the conscious business model. When asked what she meant by ‘conscious business’, she said, “when a corporation provides economic access to its employees. When labor and/or content isn’t taken without compensation. This isn’t the practice at Buzzfeed, Huffington Post and others that follow the corporate culture model. A model that hoards all the wealth at the top when all the actual work comes from the bottom. The fact is, WYV respects the people that work for us.”

Throughout July and December of 2018, rubber hit the road as WYV struggled financially. Ravneet made the executive decision to stop publishing. “If we can’t pay, we don’t publish.” She did not have the conscience to take the content from her writers without compensating them for it.

She explained further, “a lot of the work our writers produce, derive from emotional trauma, especially those from people of color. That on top of the time required to write articles should never go unpaid for. And paid the proper amount.”

Prior to the publication’s financial turmoil, Ravneet had been doing everything necessary to keep WYV afloat. “I spent two and a half years looking for funding and met with some of the biggest venture capitalist companies. I know, however, that I would never have had the opportunity to sit at these tables or have these meetings if I didn’t have the immense privilege in this space just by how I appear.”

In January 2019, WYV was able to secure funding. Not only is the publication producing some of the best content online, it is also thriving. “When I take my business forward,” Ravneet said, “I take everyone along with me.”

Currently, WYV writers are working more than twice the hours they were before and are being paid at a competitive rate.

WYV is Nothing Without Our Writers

Ravneet admits that when the publication faced adversity, her writers supported her the most.

“I cannot say enough about the entire team that got WYV where it is today, there have been many, many people who have played a significant role in getting us here, too many for me to mention them all. One person who deserves a shoutout is, WYV ex director of operations/ex co-founder, Monica Cadena. Unfortunately, due to still bootstrapping and a dwindling budget, we had to part ways mid 2018, but she was a true dedicated member of our team that helped me fine tune our output during our formative years. As we moved through the end of 2018 into 2019, Lara Witt and Sherronda Brown, now doing the jobs of 10 different people, stuck by my side and really took one for the team knowing sometimes that not being paid may occur. Luckily that didn’t happen, but for a time it was a concern. I truly, could not have got this far without any of them, I will always be eternally grateful.”

If you visit WYV’s website (which you should here), you’ll see over a dozen Black and Brown Womxn that make up the writing staff. We asked Ravneet how she was able to secure such a strong roster of writers.

“I think they work here because they understand the work that needs to be done. They understand that WYV wants their voices [amplified] because that will produce more conversations, which will continue to empower marginalized people.” She continued, “our writers will never be over-edited, we respect their words, nor will they ever be tokenized or asked to do things they don’t want to do. We respect them, they have an expertise and ability I don’t have.”

Congruent with respect, Ravneet made it a practice to not only pay writers competitive rates but since securing the investment, writers are paid the minute their work is published, a practice foreign in digital media and a practice proposed to her by WYV’s EIC, Lara Witt. “Our writers tell us that other publications often pay them a month after work has been submitted. Not here. Writers get paid on time. We have PayPal and Venmo set up so there’s no excuse for them to wait for the work they put out.”

Our suspicion on why writers join WYV is because they have a strong leader at the helm. Ravneet is fearless and gambled on herself. And won!

I’m Bananas

Ravneet is not here to make white people feel comfortable. From WYV producing content that disrupts the white aesthetic to her correcting white people on how to say her name, (it’s Ravneet, phonetically Rahvneeth) she is not here for you, Suzanne!

“People more or less ask me, ‘can you make racism, nice’ or ‘why are you all so angry,” she snickered. “And I respond, ‘Fuck you! Of course, we’re angry,’ we all ought to be angry.”

WYV has built an amazing audience that she is proud of. She acknowledges that they are genuine (and earned) and can’t be bought. But she wants more.

Admittedly though, she’s always wanted more. “I am fearless! I have nothing to lose and everything to gain at this point,” she said proudly. “I am not afraid to say how I feel. I didn’t always have this voice and used to be terrified to say what I wanted. I am not scared anymore.”

So we asked, “what do you want and what’s next for WYV?”

She responded, “I’m bananas but hear me out.”

“WYV produces vital content,” she continued. “Honestly, the work is so important and powerful. It keeps my heart pumping and keeps my brain ticking and it pushes me to be better every single day. Because unconscious bias is so real, especially if you’re from a white or Desi community. The bias that you grow up with doesn’t leave you. It’s with you everyday.”

“The root of WYV is education and how we can do better. I believe the natural path for us next is streaming! We belong in the same space as Netflix and Hulu. I want our articles to be brought to life across multimedia.”

She spoke excitedly. “Our articles can easily be docu- or web-series. There is so much that can be learned. With our content, anyone can come from any standpoint and learn without fear of exposing themselves as being ignorant and learn so much. Each time I read our pieces, I read the same as the general public. And I learn something every time.”

Considering Ravneet’s solid record of getting shit done, we wouldn’t bet against her and expect to see WYV on a streaming platform soon.

Ravneet currently resides in Los Angeles, California. She has a husband, Sumit Sharma, and two children, daughter, Ambika (9) and son, Iraj (7). You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Also, please check out WYV’s store here.